Welcome to the hundreds of new faces who signed up to read this blog in the last week - I’m grateful for your precious attention! I think most of you found me via last week’s essay ‘my smartphone stole my reality’ and my daily Notes series ‘creating instead of spending time on screens’ where I’m on day 14 of sharing pictures of something I create instead of scrolling (like this one). I’m currently writing an essay about the experience, so stay tuned for that, but today I’d love to discuss my current non-fiction read (which I invite you to read with me). Stolen Focus by Johann Hari is about the attention economy and regaining our ability to focus on what truly matters to us, so I hope you’ll find these notes thought-provoking! I’m on page 133/237 so I’ll be writing to you again in a couple of weeks time to discuss the latter half.

BOOK NOTES

The central premise of the book is that our attention is being stolen from us not just because we struggle with discipline, but because of a complex web of powerful external forces too. If you like Cal Newport’s work (like Digital Minimalism and Deep Work) you’ll probably find this one interesting too.

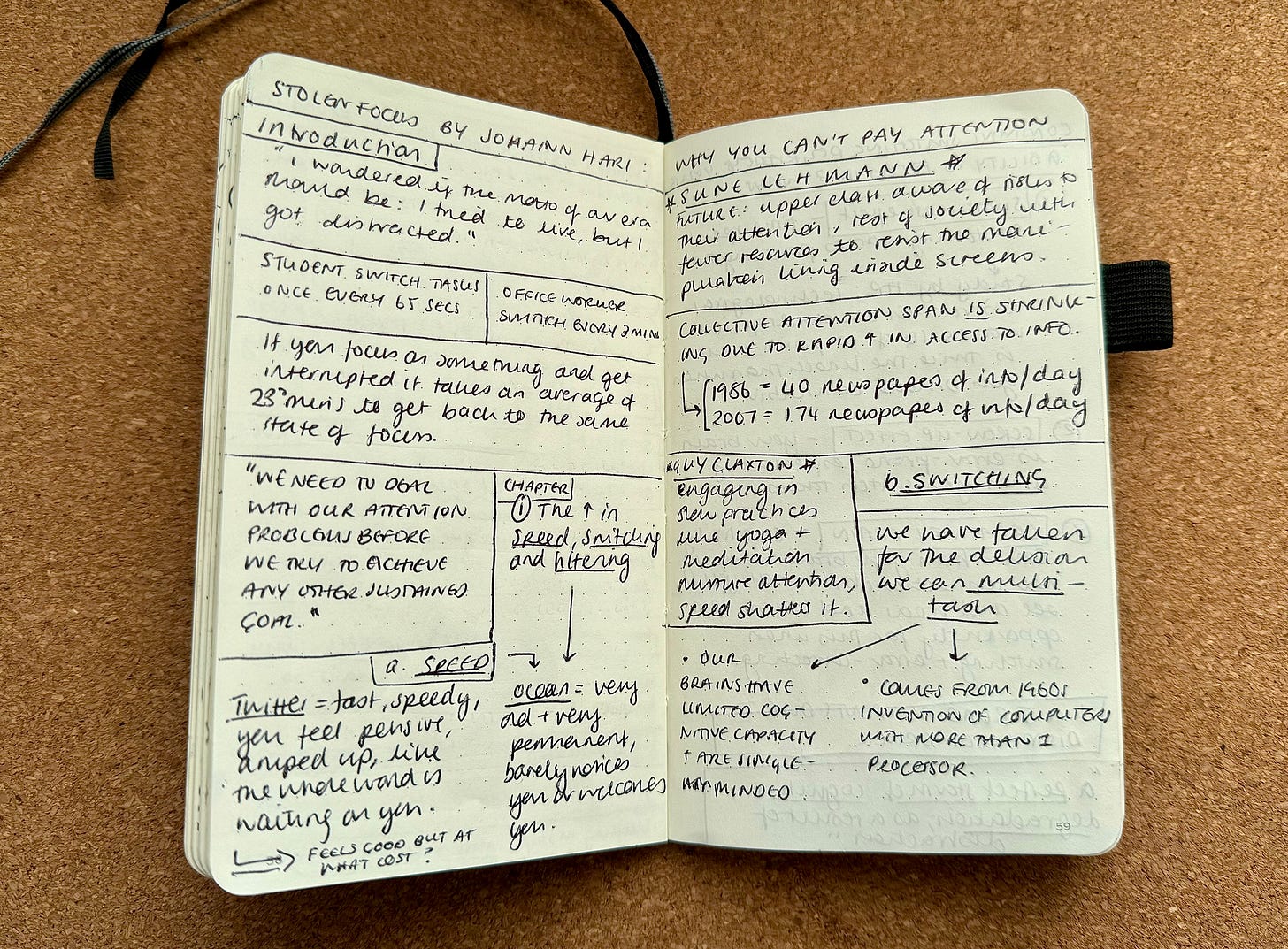

I enjoy reading someone who is similarly cynical about the role of big tech when it comes to the general population’s attention spans. He writes “I wondered if the motto of our era should be: I tried to live, but I got distracted”. As I discussed in last week’s essay, this rings true for me personally. I have time for anyone discussing the ins and outs of the attention economy because I personally believe it underpins so much of what we spend our time trying to do - productivity, efficiency, wellness, work, life. As Hari says “We need to deal with our attention problems before we try to achieve any other sustained goal”.

Hari refers to various interesting (though depressing) statistics. For example (I’m paraphrasing):

If you focus on something and get interrupted it takes on average 23 minutes to get back into the same state of focus

Students switch tasks every 65 seconds

Office workers switch tasks every 3 minutes

In 1986 each person received 40 newspapers worth of information per day, but by 2007 it increased to 174 newspapers of information per day

Technological distraction causes a drop in workers IQ of 10 points which is twice the knock than when you smoke cannabis

I enjoyed the section about multi-tasking. Hari interviewed Professor Earl Miller at MIT who said: “your brain can only produce one or two thoughts in your conscious minds at once. That’s it. We’re very single-minded. We have very limited cognitive capacity. This is because of the fundamental structure of the brain and it’s not going to change”. Earl suggests that rather than acknowledge this limitation we have fallen for the delusion that we can multi-task, explaining where the idea of multi-tasking even came from: “In the 1960s, computer scientists invented machines with more than one processor, so they really could do two things (or more) simultaneously. They called this machine-power ‘multitasking’. Then we took the concept and applied it to ourselves.” Earl goes on to conclude “We are not machines. We cannot live by the logic of machines. We are humans, and we work differently.”

A tip I picked up from Cal Newport’s book Digital Minimalism, that is covered in this one too, is “to recover from our loss of attention, it is not enough to strip out our distractions. That will just create a void. We need to strip out our distractions and to replace them with sources of flow.” Newport doesn’t specify what should replace the removal of distractions, but Hari does - he suggests distraction must be replaced by an activity that results in a state of ‘flow’. For me, this has looked like replacing social media with writing and art and reading around topics I find interesting - each of which allows me to fall into a state of ‘flow’ more easily than, for example, watching TV. The argument goes that “the more flow you experience, the better you feel” and the less likely you are to go back to social media (i.e. the distraction you are seeking to reduce or eliminate).

“I like the person I become when I read a lot of books. I dislike the person I become when I spend a lot of time on social media.”

People who make the tech that is stealing our focus often don’t use it themselves:

“They [big tech] spend a lot of their own time meditating and doing yoga. They often ban their own kids from using the sites and gadgets they design, and send them instead to tech-free Montessori schools.”

“One day, James Willians - the former Google strategist I met - addressed an audience of hundreds of leading tech designers and asked them a simple question. ‘How many of you want to live in the world you are designing?’ There was silence in the room. People looked around them. Nobody put their hand up.”

“Chamath Palihapitiya, who had been Facebook’s vice president of growth, explained in a speech that the effects are so negative that his own kids ‘aren’t allowed to use that shit’.’

“Tony Fadell, who co-invented the iPhone said: ‘I wake up in cold sweats every so often thinking, what did we bring to the world?’ He worried that he had helped create ‘a nuclear bomb’ that can ‘blow up people’s brains and reprogram them’.”

It’s important to note that research on the central question in this book - “is our collective attention span really shrinking?’ - is in its infancy. Hari refers to the largest scientific study to date conducted in 2014 and makes note of the fact it is “pioneering, so it only provides us with a small base of evidence”, but goes on to say more than half way through the book on page 176 that “we don’t have any long-term studies tracking changes in people’s ability to focus over time.” He seems to be admitting that there aren’t any long-term studies supporting the main thesis of the book (which, as a layperson, I assume equates to strength of causality and conclusions). In my view this doesn’t make the book redundant - his anecdotal reporting, qualitative interviews and references to various short-term research builds a convincing picture - but I personally would have appreciated him making this context clearer at the outset of the book.

As with any book that is widely lauded by celebrity names who don’t have any specialised knowledge about the topic I wonder how much of the success of the book is down to its PR team and not its quality. Cynical, I know - but I would have loved to see a few more social scientists or neuroscientists from the field weighing in on the review process.

BOOK CLUB DISCUSSION

What are some passages that you underlined, or ideas that particularly affected you?

Did you doubt the author's advice at some points? How come?

Did this book make you want to trial any changes in your life? What are they?

What did you think of Hari’s writing style?

I ordered it (secondhand score!) when you mentioned the book, because it sounded interesting & I like that sort of read. Honestly there's a lot I took away, even though I agree with you that it's perhaps not the most well-researched/factually correct/etc etc... I could see myself in a lot of what he said, and that was what mattered to me. I think my biggest realisation was it really sunk in this time that it isn't a personal failing on my part. The whole "What's wrong with me? Why can't I stop using my phone?" isn't just me 'being ADHD' - no, I'm being digitally and technologically manipulated and influenced to use this stuff for as many hours as possible. I would've liked to have seen more practical advice though, as to what to do about it.

I enjoyed Stolen Focus, it was a totally sufficient popular-science aggregation of thinking for the general public, and certainly more readable than Jaron Lanier's "Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now", for example.

Still, I think that Hari is quite conscious of the plagiarism scandal in his past, and the impact it's had on his image. To the point that he's written a book so citation-heavy that it detracts from the flow (pun unintended) a bit. Hari's even supplied audio of many interviews on his website, at if to cut off doubt at the pass. (https://stolenfocusbook.com/audio/).

I think Hari makes some fine points and interviews some interesting people. But as some others have commented (Hey Jennifer!), he's not the only person making them. Still, I've enjoyed reading several books on attention and technology, and mapping out where there's consensus vs. disagreement.

I'm just tucking in to Jenny Odell's "Saving Time", bit late to the game. 😁 Interested to see how it fits in with other work on the topic, as well as her first book, "How to Do Nothing".